Please fill out the details below to receive information on Blue Wealth Events

"*" indicates required fields

There’s no way to sugar coat things: our economy is experiencing a biological shakedown. In response, the RBA convened a special meeting last week to decrease the cash rate target again. They have now trimmed 75 basis points from the cash rate this year – the same amount trimmed last year. That puts us at an all-new record low of 0.25 percent. By comparison, the United States is also at 0.25 percent, United Kingdom 0.1 percent and Canada 0.75 percent. More heavily reported on is the downward trajectory of financial markets, which have lost trillions since the international outbreak of COVID-19. The ASX200, an index representing the bulk of Australian listed shares, has dropped by more than a third in the space of a month.

But what does this all mean in the context of property ownership and property investment? A couple of weeks ago, we discussed how the property market was, and wasn’t, being impacted by COVID-19. We made note of anecdotes impacting individual property sales, such as Chinese buyers being unable to attend high-end property auctions. What we didn’t cover, however, is how residential real estate reacts to economic volatility and uncertainty like what we are experiencing now.

The good news? Approximately 70 percent of Australian housing is occupied by their owner, which means these homes aren’t investments the way shares and other financial assets are. Demand for housing isn’t directly shaken by poor performance in the stock market because at the end of the day, you still have to go somewhere after a day’s work. Property is also slow. Even when the economy is in turmoil, you can’t just sell a house on an impulse like you can with shares. Spur of the moment decisions (such as a decision to sell) are followed by weeks or months of a sales campaign.

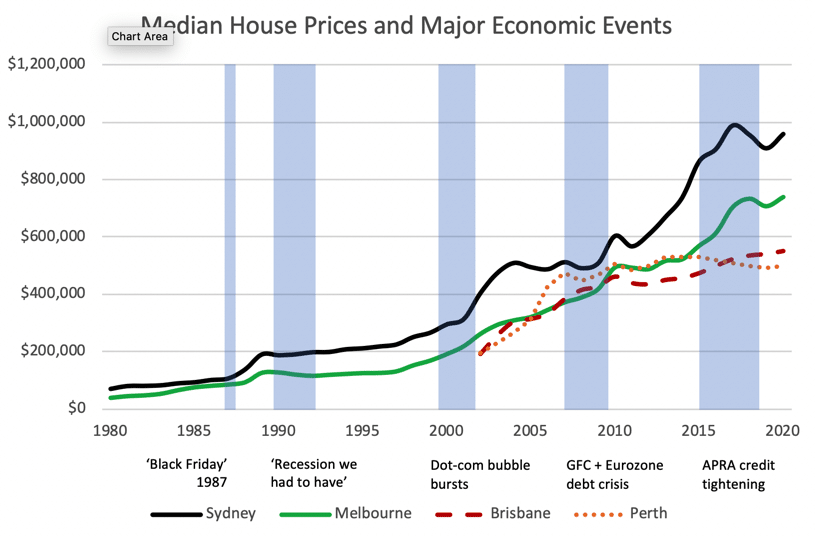

Nevertheless, poor economic performance does influence the property market in interesting ways. Some of these influences are bad, others good and the rest are somewhat benign. Examples include short-term changes to credit, sentiment, migration and others. Over the coming weeks, our research blog will uncover these influences which have been integrated into our research model over our years in operation. For the time being, let’s look at how residential property has performed in our cities during recent economic panics.

Source: Blue Wealth Property, Stapledon (2012), ABS

As is evident from the provided chart, not all property markets act the same way at the same time. Nevertheless, what Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane have in common over the past forty years is resilience in the face of economic uncertainty. Further, economic crises are often followed by particularly strong residential property performance. Often, this is a function of both undersupply and credit, as was the case in Sydney after the global financial crisis. With the supply of new housing already reaching a critically low point, one of the most significant impacts of the COVID-19 scare on the real estate market could be further undersupply, especially if rates of immigration are stimulated by those who feel Australia is a safer place to live. In a record-low interest rate environment, this could place more upward pressure on property prices once COVID-19 is under control.